Southerner Elizabeth Van Lew Supported the Union

Richmond, Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy, had a crafty Union spy operating within it to subvert its secessionist rebel efforts. The spy was a woman named Elizabeth Van Lew.

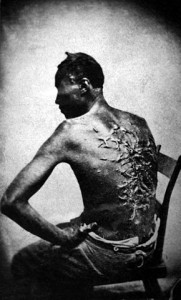

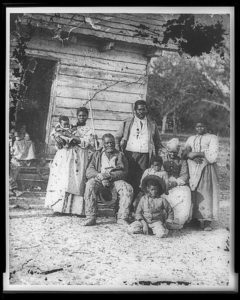

Van Lew’s parents were from the North and her father John came to Richmond with his wife Eliza to become a hardware merchant. Their daughter Elizabeth was born in Richmond in 1818. John Van Lew’s hardware business prospered and the family lived in the upscale Church Hill neighborhood of Richmond. The family attended the historic Saint John’s Episcopal Church and the Van Lews became part of Southern society. They owned many slaves, despite mother Eliza and daughter Elizabeth believing slavery was evil and wanting it to end.When the Southern states began seceding from the Union after Abraham Lincoln’s election as president in November 1860, young Elizabeth thought secession was a bad policy. Van Lew supported the Union, the Republican Party, and the abolition of slavery. She thought the opposite of what most all Southerners thought. When the Civil War began, Elizabeth had the means and opportunity to move North and be with other family members. Instead, Elizabeth chose to stay in Richmond, the seat of the Confederacy. She had plans.

She Gave Aid and Help to Libby Union Prisoners of War

Richmond’s Libby Prison held Union officer prisoners of war under difficult and overcrowded conditions. The prisoners suffered from disease and malnutrition, and the prison had a high death rate. Elizabeth Van Lew visited the prison pretending to be a loyal Southern lady living up to her Christian faith and womanly concern for others. She provided help and aid to the suffering and needy Yankee prisoners. Elizabeth used her family’s wealth to bribe guards and officials to gain favors and assistance for the prisoners. What she sneakily did, with her philanthropist and caring cover of helping the prisoners by giving them food and medicine, was to also help them escape.

Van Lew gathered information from the prisoners and passed it over to Union forces. In March 1862, President Jefferson Davis clamped down on Richmond with an iron fist of martial law. Many people thought to be Union supporters in the Confederate capital were arrested. Elizabeth Van Lew could no longer visit Libby Prison and give aid to the prisoners. This did not stop her clandestine pro-Union efforts in Richmond. She changed her tactics.

Learn Civil War History Podcast: Elizabeth Van Lew – A Union Spymaster in Richmond

Listen and learn about Elizabeth Van Lew.

The Richmond Underground

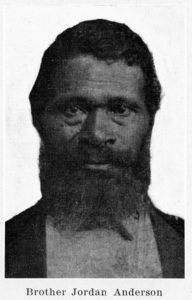

With Van Lew’s leadership, the Richmond Underground was organized as a Union spy ring. The Richmond Underground was a secret spy network made-up of whites and African-Americans. It helped Union prisoners escape from imprisonment and helped pro-Union Southerners flee to the North. Van Lew and other workers of the Richmond Underground arranged for escapees to have shelter in safe houses and provided them with disguises. The Van Lew family home was used as a safe house. Some members of the Richmond Underground helped escapees by accompanying and guiding them to safety within Union lines.

Her Spy In the Confederate White House

When Elizabeth Van Lew passed away in 1900, it was rumored that she’d had an African-American servant planted and working as a spy in the Confederate White House during the Civil War. This proved to be true. Mary Jane Richards Denham was an African-American lady whom the wealthy Van Lews had sent North for her education, and then on to Liberia. The Van Lews had Mary Jane return to Richmond shortly before the Civil War began. On her return to the South, with help from the Van Lews, Denham devised an identity as Mary Elizabeth Bowser to avoid detection and capture by Confederate authorities.Mary Jane Richards Denham/Mary Elizabeth Bowser became an active spy in the Confederate White House. Those in the Confederate White House assumed she was a slave and illiterate. Conversations were not hidden from her. Mary would listen attentively and read what papers she could to gather information. After the Civil War, using the name “Richmonia Richards,” she gave a speech that was written up in a newspaper article. In her speech, she told of going, “into President Davis’s house while he was absent, seeking for washing” and then finding her way to an office where she, “opened the drawers of a cabinet and scrutinized the papers.”

Federal Service and Military Recognition

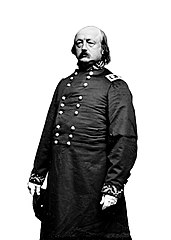

Major General Benjamin F. Butler recruited Elizabeth Van Lew and other Southern Unionists into Federal service. Van Lew’s spy efforts reached their peak. The Van Lew family home in Richmond became the heart and center of the Richmond Underground spy network. Van Lew was known as a spymaster. Her group of spies used code words and invisible ink in messages hidden in their clothing and shoes. These messages contained valuable intelligence for Union officers. As General Grant fought against the trench lines stretching from Petersburg to Richmond, the Richmond Underground provided him with information. This information included important news about the Confederate movement of men and matériel going back and forth in the east and the Shenandoah Valley.After the Civil War, George H. Sharpe, the chief of military intelligence for the Army of the Potomac, wrote about contributions that spymaster Elizabeth Van Lew made to the Union. Sharpe wrote, “for a long, long time, she represented all that was left of the power of the U. S. Government in the city of Richmond.”