“Letter From A Freedman” (1865)

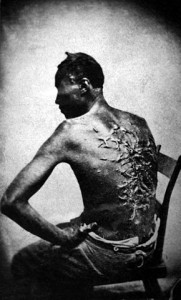

Slaves were not treated as human beings in the slave-holding South. They were treated as animals, nothing more than beasts of burden to their owners. The lives of the slaves were like hell on Earth. The exploitation of their toil made for high profits and riches for their owners. Slavery was called the “Peculiar Institution,” but a more truthful name would have been the “Cruel Institution.”

If a slave gained his freedom, why would he ever voluntarily return to work for his former master?

What Was The Life Of A Slave Like?

- The Peculiar Institution of slavery was a brutal institution. Slaves were whipped, beaten, branded, chained, mutilated, raped, imprisoned, or killed by their masters.

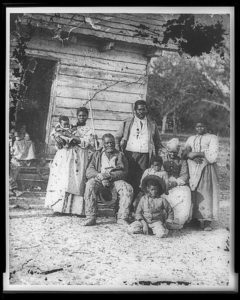

- The living conditions of the slaves were miserable. They had to rely on their owners for shelter and the owner’s concern for his slaves varied. Some owners would provide their slaves with small shacks or huts, some did not and the slaves had to fashion their housing out of whatever materials might be provided or scrounged up.

- Most common as shelter for the slaves was a simple one-room shack that was cold in the winter and hot in the summer. As many as ten slaves might be crowded into the same shack. Sickness and disease spread easily in these living conditions.

- Slaves were not taught to read or write. Some states prohibited slaves from learning to read and write because it was feared such knowledge would encourage the slaves to rebel, rise up, or escape. Uneducated slaves had to depend on their owners and this helped to establish the owner’s dominance and control over his slaves.

- Frederick Law Olmsted was a landscape architect, journalist, and social critic. He was in Mississippi in 1853 when he wrote about what life for a slave was like; “A cast mass of the slaves pass their lives, from the moment they are able to go afield in the picking season till they drop worn out in the grave, in incessant labor, in all sorts of weather, at all seasons of the year, without any other change or relaxation than is furnished by sickness, without the smallest hope of any improvement either in their condition, in their food, or in their clothing, which are of the plainest and coarsest kind, and indebted solely to the forbearance or good temper of the overseer for exception from terrible physical suffering.”

- If a slave complained about his or her housing, clothing, care, health, work, or food, then punishment would most likely follow. A whipping or worse was given to the slave who complained. The owner’s dominance over the slave was always demonstrated and kept strong. Complaining slaves suffered for their courage and boldness of protesting to their owner.

- The beds of the slaves simply laid on top of the dirt inside their shacks or huts. Their beds were made of nothing more than straw, old rags, or whatever might be found by the slave that could possibly be used as bedding. The slaves typically had little or no furniture, and what furniture they did have they made for themselves. Perhaps a broken and worn out throw-away piece of furniture from the plantation house might be obtained by the slaves, if they were lucky.

- The slaves who worked in the plantation house for the owner’s family usually had a bit better and easier life than the slaves who worked outside in the fields. The house slaves usually had better living quarters, better food, and better clothing than the slaves working in the fields for the master.

- Cooking pots and pans were usually hard to come by for the slaves, utensils and such were scarce items for the slaves. The slaves would innovate and find other ways to cook their food. A “calabash” was a pumpkin or gourd shell hollowed out to create a large food bowl used for cooking or serving. The owners did not want to spend any money unnecessarily on their slaves, making cornbread and fatty, tough, meat regular items of sustenance for the slaves. Some owners allowed their slaves to have gardens so they could grow their own food. The slaves would have to tend to these gardens after working all day in the field.

- The slave owners would provide a pair of shoes a year, and allocate out underwear, shirts, trousers, dresses, coats or jackets, for their slaves. A slave’s clothing often fit poorly being either too large or too small, and made of coarse, rough, and uncomfortable material.

- The slaves worked from sunrise to sunset and if there was a full moon, then into the night as well. Some owners worked their slaves every day, some might give their slaves Sunday off (some owners allowed their slaves to have church services), some might give their slaves one day off every month or after some other length of time. Working slaves meant money and profit for the owner. Free time for a slave was a precious thing to have.

“When I was three or four years old my mother was whipped to death by the mistress with a cowhide whip.”

– Former slave Henry Walton, Marshall County, Mississippi.

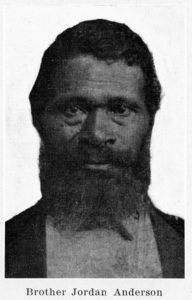

Who Was Jourdon Anderson?

Jourdon Anderson was born a slave in Tennessee sometime around 1825. When he was only seven or eight-years-old he was sold by his first owner to General Paulding Anderson of Wilson County, Tennessee. General Anderson then gave Jourdon to his son Patrick Henry Anderson to be his servant and playmate. Patrick Henry was about the same age as his servant Jourdon.Patrick Henry Anderson grew up to be known as Colonel P. H. Anderson, his slave Jourdon grew up and got married. Jourdon Anderson and his wife Mandy had eleven children. Jourdan would continue to be Colonel P. H. Anderson’s slave until Yankee soldiers freed him during the Civil War when they camped on the Anderson plantation in 1864. After becoming a freeman, Jourdon eventually lived in Dayton, Ohio where he worked at various times as a janitor, a carriage driver, and in a stable taking care of horses. In 1894 Jourdon became a sexton at the Wesleyan Methodist Church.

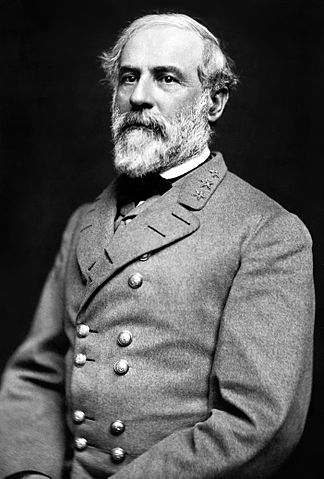

The Civil War brought about the end of slavery. With the harvest season coming soon the late summer of 1865, Colonel P. H. Anderson’s Tennessee plantation was in bad shape and the colonel was in debt. The colonel desperately needed the help of his former slave and childhood playmate Jourdon for the hard work of bringing in the crops. In August Colonel P. H. Anderson sent a letter to Jourdon Anderson asking him to return to the plantation in Tennessee and work for him harvesting the crops.

Jourdon Anderson dictated a sardonic response letter to his former master. Jourdon’s humorous, mocking, and scornful letter to his former master was published in the Cincinnati Commercial and the New York Daily Tribune, making Jourdon a media sensation of his day. Colonel P. H. Anderson had to sell his plantation at a fraction of its worth to pay off debt. He died only a few years later when he was forty-four-years-old. The freeman Jourdon Anderson died on April 15, 1907.

Explanatory notes for Jourdon’s letter:

* George Carter was a carpenter.

* Miss Martha is Colonel P. H. Anderson’s wife.

* Miss Mary is Colonel P. H. Anderson’s daughter.

* Henry is most likely Colonel P. H. Anderson’s son, Patrick Henry Anderson, Jr.

* Matilda and Catherine are Jourdon Anderson’s daughters who did not go to Ohio.

* Valentine Winters was a banker, and friend of Jourdon Anderson.

* There are multiple ways Jourdon Anderson’s first name is spelled. “Jourdon” is used here in this post.

Jourdon Anderson’s Letter To His Old Master

Dayton, Ohio,

August 7, 1865

To My Old Master, Colonel P.H. Anderson, Big Spring, Tennessee

Sir: I got your letter, and was glad to find that you had not forgotten Jourdon, and that you wanted me to come back and live with you again, promising to do better for me than anybody else can. I have often felt uneasy about you. I thought the Yankees would have hung you long before this, for harboring Rebs they found at your house. I suppose they never heard about your going to Colonel Martin’s to kill the Union soldier that was left by his company in their stable. Although you shot at me twice before I left you, I did not want to hear of your being hurt, and am glad you are still living. It would do me good to go back to the dear old home again, and see Miss Mary and Miss Martha and Allen, Esther, Green, and Lee. Give my love to them all, and tell them I hope we will meet in the better world, if not in this. I would have gone back to see you all when I was working in the Nashville Hospital, but one of the neighbors told me that Henry intended to shoot me if he ever got a chance.I want to know particularly what the good chance is you propose to give me. I am doing tolerably well here. I get twenty-five dollars a month, with victuals and clothing; have a comfortable home for Mandy,—the folks call her Mrs. Anderson,—and the children—Milly, Jane, and Grundy—go to school and are learning well. The teacher says Grundy has a head for a preacher. They go to Sunday school, and Mandy and me attend church regularly. We are kindly treated. Sometimes we overhear others saying, “Them colored people were slaves” down in Tennessee. The children feel hurt when they hear such remarks; but I tell them it was no disgrace in Tennessee to belong to Colonel Anderson. Many darkeys would have been proud, as I used to be, to call you master. Now if you will write and say what wages you will give me, I will be better able to decide whether it would be to my advantage to move back again.

As to my freedom, which you say I can have, there is nothing to be gained on that score, as I got my free papers in 1864 from the Provost-Marshal-General of the Department of Nashville. Mandy says she would be afraid to go back without some proof that you were disposed to treat us justly and kindly; and we have concluded to test your sincerity by asking you to send us our wages for the time we served you. This will make us forget and forgive old scores, and rely on your justice and friendship in the future. I served you faithfully for thirty-two years, and Mandy twenty years. At twenty-five dollars a month for me, and two dollars a week for Mandy, our earnings would amount to eleven thousand six hundred and eighty dollars. Add to this the interest for the time our wages have been kept back, and deduct what you paid for our clothing, and three doctor’s visits to me, and pulling a tooth for Mandy, and the balance will show what we are in justice entitled to. Please send the money by Adams’s Express, in care of V. Winters, Esq., Dayton, Ohio. If you fail to pay us for faithful labors in the past, we can have little faith in your promises in the future. We trust the good Maker has opened your eyes to the wrongs which you and your fathers have done to me and my fathers, in making us toil for you for generations without recompense. Here I draw my wages every Saturday night; but in Tennessee there was never any pay-day for the negroes any more than for the horses and cows. Surely there will be a day of reckoning for those who defraud the laborer of his hire.

In answering this letter, please state if there would be any safety for my Milly and Jane, who are now grown up, and both good-looking girls. You know how it was with poor Matilda and Catherine. I would rather stay here and starve—and die, if it come to that—than have my girls brought to shame by the violence and wickedness of their young masters. You will also please state if there has been any schools opened for the colored children in your neighborhood. The great desire of my life now is to give my children an education, and have them form virtuous habits.

Say howdy to George Carter, and thank him for taking the pistol from you when you were shooting at me.

From your old servant,

Jourdon Anderson.

Learn Civil War History Podcast Episode Seven: Freedman Jourdon Anderson Writes A Letter To His Old Master

Spotify

“My mammy… belong to old man Weathersby in Amite County. He was de meanes’ man what ever lived. My pappy was sol’ befo’ I was born. I doan know nothin’ ’bout him. . . . Mammy said when I was jes big ’nough to nuss an’ wash leetle chulluns, I was sol’ to Marse Hiram Cassedy an’ dat man give me ter his darter, Miss Mary, to be her maid. . . . I was never whupped afte’ I went to Marse Cassedy.”

– Former slave Fanny Smith Hodges, Pike County, Mississippi.

“I seed slavery from all sides. I’se seed ’em git sick and die an’ buried. I’se seed ’em sole [sold] away from der loved ones. I’se seed ’em whipped by de overseers, an’ brung in by de patrol riders. I’se seed ’em cared fo’ well wid plenty ter eat an’ clo’se ter keep ’em warm, an’ wid good cabins ter live in.”

– Former slave Rosa Mangum, Simpson County, Mississippi.

Slave Narratives Tell First-Hand What Life For A Slave Was Like

The Federal Writers’ Project was part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Works Projects Administration created to help get people back to work during the Great Depression of the 1930s. The Federal Writers’ Project recorded and transcribed a compilation of 3,500 oral narratives and histories told by former slaves. These first-hand slave narratives provide us with great insight as to what life was like for a slave in the South.

Here are two videos of actors and celebrities voice-acting some of the stories told in the Federal Writers’ Project slave narratives. The original recordings of the slave narratives can be difficult to understand because of scratchy recordings, the poor recording technology of the 1930s as compared to today’s, and the sometimes hard to understand voices of the former slaves who were then aged into their 80s or 90s, some of them were even over 100-years-old.

Slave Memories Part 1

Slave Memories Part 2

“When you is a slave, you ain’t got no mo’ chance than a bullfrog.”

– Former slave Virginia Harris, Coahoma County, Mississippi.

More posts:

Free And Slave States Map – State, Territory, And City Populations

Slavery

Thirteenth Amendment Abolishes Slavery

Robert Smalls

1850 Fugitive Slave Law

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!