How Many Died in the Civil War?

A casualty is someone injured, killed, captured, or missing in a military engagement. The Civil War had plenty of all these. The casualty totals in the Civil War can only be treated as estimates. The exact numbers cannot be exactly known.

Due to exhaustive research by many credible and earnest Civil War scholars, the casualty numbers presented here can be considered to be as accurate as possible. I have relied on trustworthy sources for the numbers and statistics I share in this post. The exact number of Civil War casualties will forever be a topic for debate.

One fact we can be certain of regarding Civil War casualty counts, the carnage of the Civil War was immense. War and disease provided the Grim Reaper with all he desired.

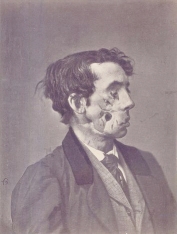

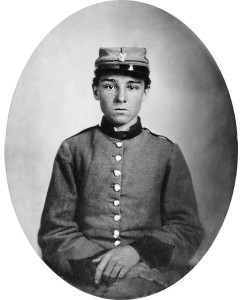

Let us not neglect to know that the cold numbers and statistics shown in this post are facts that represent real people. People who fought in a vicious war, who bled red blood whether they were clothed in blue or gray. People who lost limbs or were severely disfigured, people who died miserable, slow deaths of disease or injury, people who perished instantaneously in groups during battle, or slowly had life ebb away as they sprawled alone and incapacitated in the aftermath of a major battle or minor skirmish. Many died agonizing and feverish deaths of disease. These numbers are human beings.

Do We Know How Many Died?

The quick and simple answer is that no one knows for sure exactly how many died in the Civil War, neither for the North or the South. An estimate of the deaths in the Civil War is 623,026. This means that of men of service age, one out of eleven men died during the Civil War years between 1861 and 1865.

Below is a chart showing how the Civil War compares in total deaths to other wars:

Deaths in American Wars

| War | Deaths |

| Revolutionary War | 4,435 |

| War of 1812 | 2,260 |

| Mexican | 13,283 |

| Civil War | 623,026 |

| Spanish-American | 2,446 |

| World War I | 116,516 |

| World War II | 406,742 |

| Korea | 54,246 |

| Vietnam | 57,939 |

How Many Casualties in the Civil War?For both sides in the Civil War, 471,427 can be considered as a minimum number of those wounded. When added to the estimate of 623,026 deaths, the total estimate of Civil War casualties is 1,094,453. |

Greatest Union Battle Losses

+ Not including South Mountain and Crampton’s Gap.

++ Includes Chantilly, Rappahannock, Bristoe Station, and Bull Run Bridge.

Source of table: William E. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1861-1865

The Union Armies lost 110,070 killed or mortally wounded, and 275,175 wounded; for a total of 385,245. This does not include the missing in action. Of the 110,070 deaths from battle, 67,058 were killed on the field and the remaining 43,012 died of wounds.

This table shows how this loss was divided among the different arms of the service:

| Service | Officers | Enlisted Men | Total | Ratio of Officers to Men |

| Infantry | 5461 | 91424 | 96885 | 01:16.70 |

| Sharpshooters | 23 | 443 | 466 | 01:17.70 |

| Cavalry | 671 | 9925 | 10596 | 01:14.70 |

| Light Artillery | 116 | 1701 | 1817 | 01:14.60 |

| Heavy Artillery | 5 | 124 | 129 | 01:24.80 |

| Engineers | 4 | 72 | 76 | 01:18.00 |

| General Officers | 67 | —- | 67 | —- |

| General Staff | 18 | —- | 18 | —- |

| Unclassified | —- | 16 | 16 | —- |

| Total | 6365 | 103705 | 110070 | 01:16.20 |

Source of table: William E. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1861-1865

The losses in the three main categories of Union troops were:

| KILLED OR DIED OF WOUNDS | ||||

| Class | Officers | Enlisted Men | Total | Ratio of Officers to Men |

| Volunteers | 6078 | 98815 | 104893 | 01:16.20 |

| Regulars | 144 | 2139 | 2283 | 01:14.80 |

| Colored Troops | 143 | 2751 | 2894 | 01:19.20 |

| Total | 6365 | 103705 | 110070 | 01:16.30 |

Source of table: William E. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1861-1865

DIED BY DISEASE. NOT INCLUDING DEATHS IN PRISONS.

| Class | Officers | Enlisted Men | Total | Ratio of Officers to Men |

| Volunteers | 2471 | 165039 | 167510 | 02:06.70 |

| Regulars | 104 | 2448 | 2552 | 01:23.50 |

| Colored Troops | 137 | 29521 | 29658 | 04:35.50 |

| Total | 2712 | 197008 | 199720 | 02:12.60 |

Source of table: William E. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1861-1865

Deaths in the Union Army, from all causes, as officially classified.

DEATHS FROM ALL CAUSES:

| Cause | Officers | Enlisted Men | Aggregate |

| Killed, or died of wounds | 6365 | 103705 | 110070 |

| Died of disease | 2712 | 197008 | 199790 |

| In Confederate prisons | 83 | 24783 | 24, 866 |

| Accidents | 142 | 3972 | 4114 |

| Drowning | 106 | 4838 | 4, 944 |

| Sunstrokes | 5 | 308 | 313 |

| Murdered | 37 | 483 | 520 |

| Killed after capture | 14 | 90 | 104 |

| Suicide | 26 | 365 | 391 |

| Military executions | 267 | 267 | |

| Executed by the enemy | 4 | 60 | 64 |

| Causes known, but unclassified | 62 | 1972 | 2034 |

| Cause not stated | 28 | 12093 | 12121 |

| Aggregate | 9, 584 | 349, 944 | 359528 |

NOTE: The deaths from accidents were caused, principally, by the careless use of fire-arms, explosions of ammunition, and railway accidents; in the cavalry service, a large number of accidental deaths resulted from poor horsemanship.

Source of table: William E. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1861-1865

DEATHS IN CONFEDERATE ARMIES

James B. Fry, United States Provost Marshal-General, provides a report in 1865-1866 that includes a tabulation of Confederate losses. Fry’s report is compiled from the muster-rolls which are on file in the Bureau of Confederate Archives. This report is incomplete, as Confederate records can be, and often are, spotty. For example, in these records the Alabama rolls are mostly missing. Nonetheless, the numbers are worth noting. From General Fry’s report, the following tables were created by William E. Fox in his Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1861-1865:| Killed | |||

| STATE | Officers | En. Men | Total |

| Virginia | 266 | 5062 | 5328 |

| North Carolina | 677 | 13845 | 5522 |

| South Carolina | 360 | 8827 | 9187 |

| Georgia | 172 | 5381 | 5553 |

| Florida | 47 | 746 | 793 |

| Alabama | 5 | 538 | 552 |

| Mississippi | 52 | 5685 | 5807 |

| Louisiana | 70 | 2548 | 2618 |

| Texas | 28 | 1320 | 1348 |

| Arkansas | 54 | 2061 | 2165 |

| Tennessee | 99 | 2016 | 2115 |

| Regular C. S. Army | 35 | 972 | 507 |

| Border States | 92 | 1867 | 1959 |

| Totals | 2086 | 50868 | 52954 |

Source of table: William E. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1861-1865

| Died of Wounds | |||

| STATE | Officers | En. Men | Total |

| Virginia | 200 | 2319 | 2519 |

| North Carolina | 330 | 4821 | 5151 |

| South Carolina | 257 | 3478 | 3735 |

| Georgia | 50 | 1579 | 1719 |

| Florida | 16 | 490 | 506 |

| Alabama | 9 | 181 | 190 |

| Mississippi | 75 | 2576 | 2651 |

| Louisiana | 42 | 826 | 868 |

| Texas | 13 | 528 | 541 |

| Arkansas | 27 | 888 | 915 |

| Tennessee | 49 | 825 | 874 |

| Regular C. S. Army | 27 | 441 | 468 |

| Border States | 61 | 672 | 733 |

| Totals | 1552 | 20324 | 21570 |

Source of table: William E. Fox, Regimental Losses in the American Civil War, 1861-1865

The Horror of the Civil War: Wounds, Dying, and Death

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!