What Was Bleeding Kansas?

Would The Kansas Territory Join The Union As A Slave Or Free State?

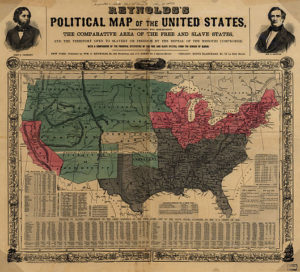

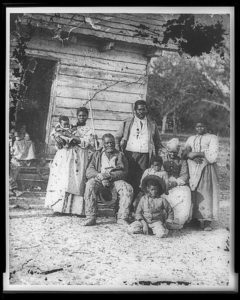

Slavery was the burning issue in the Kansas Territory during the 1850s. As the United States grew west toward the Pacific Ocean the South wanted newly admitted states to have slavery, while the North wanted new states to be free. The North wanted slavery to remain in the South or for it to end in the United States.

The Kansas-Nebraska Act drafted by Senator Stephen A. Douglas passed in the United States Congress on May 30, 1854. This act created the territories of Kansas and Nebraska, ended the 36°30´latitude boundary line created by the Missouri Compromise of 1820 used to divide slave from free territory, and let the people in the territories of Kansas and Nebraska determine by popular sovereignty (by vote) whether or not they would enter the Union as a free or slave state. Under the Missouri Compromise the Kansas Territory would have become a free state. Now there was a sea-change as the Kansas-Nebraska Act made it possible for Kansas to enter the Union as a slave state.

Anti-slavery support within Nebraska was strong enough to make certain that popular sovereignty would bring Nebraska into the Union as a free state. This was not so in Kansas, where the Kansas-Nebraska Act resulted in a violent free-for-all guerrilla war between pro-slavery and anti-slavery supporters. Besides votes, guns, knives, fire, terror, murder, lawlessness, and broadswords would also influence the decision of Kansas entering the Union as a free or slave state.

A violent territorial guerrilla civil war began in the Kansas Territory as both pro-slavery and anti-slavery settlers flooded into Kansas so their votes would decide Kansas’ fate. Kansas becoming either a slave or a free state was important because its status would tip the balance of power between the slave and free states in the United States Senate. Although there were slaves in the Kansas Territory, it was made up primarily of small farmers who did not own slaves and who had no great desire to see slavery come to Kansas.

Hundreds of armed Missouri pro-slavery supporters (Border Ruffians) crossed the border into the Kansas Territory in late March 1855 to illegally vote for slavery. They stuffed ballot boxes with fictitious votes for Kansas pro-slavery representatives. The result of this shady election was that the territorial legislature became pro-slavery and it enacted pro-slavery laws. One such law made it a capital offense for anyone to even have abolitionist literature in their possession. Anti-slavery supporters (Jayhawkers) soon responded by forming their own anti-slavery government to oppose the pro-slavery government. From Washington, D.C., there came no help for the anti-slavery cause as President Franklin Pierce’s administration did not recognize the Kansas Territory’s anti-slavery government as legitimate.

Anti-slavery supporters from the North came to the Kansas Territory to gain the voting advantage. Violence soon followed as the pro-slavery and anti-slavery factions clashed. Stores were robbed, homes and barns burned, people beaten, people shot, people killed, and towns terrorized in the Kansas Territory. Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune newspaper wrote about, “Bleeding Kansas” or “Bloody Kansas” and this became a name for the conflict.

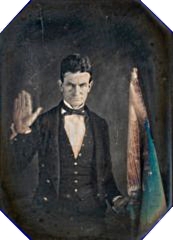

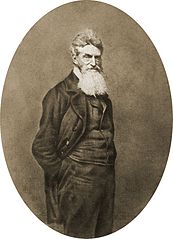

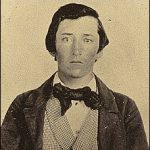

Into this boiling cauldron of trouble came a man of Ohio who believed he was an instrument of God. This man was an abolitionist, but he was not a pacifist. He was a man of action who hated slavery and would kill for his beliefs. He believed he was to do God’s work and break the jaw bones of pro-slavers. John Brown would add to the blood of Bleeding Kansas.

Who Was John Brown?

Learn Civil War History Podcast – Episode One: John Brown Quotes

Much has been written and said about John Brown. John Brown is a complex character. I don’t think anyone has completely figured him out. I suppose in regard to John Brown, it’s always up to the individual studying about him to draw his or her own conclusions as to what his character was like. Some will see him as a martyr, a man willing to go to the gallows in his effort to bring freedom to the slaves, a religious fanatic, an abolitionist, a Bible-waver with a strong faith in God. Others will see him as nothing but a crazed madman, one willing to shed other’s blood, a cold-blooded killer. A weapon-waver willing to harm others to advance his beliefs.

“Old John Brown…agreed with us thinking slavery wrong. That cannot excuse violence, bloodshed, and treason. It could avail him nothing that he might think himself right.”

…Abraham Lincoln

On May 9, 1800, Owen and Ruth Brown welcomed their son John into the world. The Brown family lived in Torrington, Connecticut where Owen made his living as a tanner and a shoemaker. Faith played a major role in the lives of the Browns. The Browns were Congregationalists, members of a Protestant church where each congregation is managed by self-governing its own affairs democratically and independently. Congregationalist believe in the Bible and Jesus, but each member of the church has the “full liberty of conscience in interpreting the Gospel” as defined in the church’s “The Art and Practice of the Congregational Way.” Owen and Ruth’s baby son John, would grow to become a bold man who would act on his interpretation of the Gospel with violence.

Ohio became a state on March 1, 1803. Owen Brown moved his family from Connecticut to Hudson, Ohio in June 1805 where Owen made a living for his family as a tanner. Hudson was a small town in the raw and tough frontier-land of the Connecticut Western Reserve of Northeast Ohio. Hudson was settled by David Hudson from Goshen, Connecticut in 1799. The Brown’s first year in Hudson was difficult. The family lived in a cold and drafty log cabin their first winter and survived by eating wild game and food borrowed from neighbors. The Browns cleared land the following spring and planted corn, but the seedlings were mostly lost to frost and wild animals. John Brown’s mother Ruth died three years later during childbirth. Father Owen remarried the next year, he made money now working as a tanner and by providing beef to General William Hull during the War of 1812.

Young John Brown would grow up in Hudson, Ohio and his life there would be one of sadness and loss. John worked at his father’s Hudson tannery and his school attendance was sparse. He was in Massachusetts and Connecticut for short times, but ended up returning to Hudson to open his own tannery with a half-brother. John Brown and Dianthe Lusk were married on June 21, 1820. John and Dianthe would have seven children together but two of their children died in childhood. Brown took Dianthe to Pennsylvania where she died giving birth to their seventh child in 1832. John Brown married Mary Ann Day in 1833 and they had thirteen children. Only six of Brown’s children with Mary Ann would live to adulthood.

Hudson was a town with strong abolitionist and anti-slavery leanings. Hudson was a town on the Ohio frontier where the National Antislavery Society had influence and followers. John Brown became a young man in Hudson with definite political, religious, and moral convictions. Brown was a supporter of John Quincy Adams. Adams favored the neo-Federalist American system, was a Calvinist, and was opposed to slavery. John Brown felt that slavery was a “a great sin against God” and it was his Christian duty to help runaway slaves escape to freedom in Canada. John Brown let it be known that he would welcome and protect runaways who made their way to his Ohio home. It’s known that Brown helped at least one runaway gain his freedom.

A pro-slavery mob murdered newspaperman and anti-slavery supporter Elijah Lovejoy on November 7, 1837, in Alton, Illinois. At Hudson’s Congregational Church a prayer meeting was held to recognize Lovejoy’s martyrdom. John Brown sat on a back pew of the church quietly listening during the prayer meeting. As the prayer meeting came to a close, Brown stood up, raised his right hand, and made a vow to fight against slavery declaring, “Here, before God, in the presence of these witnesses, from this time, I consecrate my life to the destruction of slavery.” John Brown lived up to his vow to consecrate his life to the destruction of slavery. Brown would hang on December 2, 1859, for his Harpers Ferry Raid, a poorly devised plan by Brown to take over a Federal arsenal, arm slaves, and set them free.

In August 1855 abolitionist John Brown was traveling from North Elba, New York back to Hudson where his father Owen was waiting his arrival. John Brown was on his long way to Osawatomie, Kansas and Hudson was only a side-stop. In Kansas, Brown would join with other family members who were living there and hoping to make a new prosperous life off the rich Kansas land.

Father Owen was now eighty-four-years-old and although his mind was sharp and clear, his health was poor and failing. Owen became concerned about his son during John’s visit to Hudson. Owen wrote to a daughter in Osawatomie saying of John, “He has something of a warlike spiret [sic], I think as much as necessary for defence I will hope nothing more.” Old man Owen Brown was correct with his apprehension concerning his son John’s “warlike” intentions in Kansas.

While visiting Ohio, John Brown obtained money and weapons to take to Kansas. Brown indeed had a warlike spirit and the weapons he obtained in Ohio would be used in Kansas for more than mere defence. John said goodbye to his aged father and departed the Northeast Ohio small town of Hudson, a hotbed of abolition itself with Owen actively involved in the cause. Owen gave his eldest son forty dollars, John badly needed the money. This would not be the last time Owen would give his son money, but it was the last time the father and son would meet in person.

John Brown was an abolitionist who believed violence was justified to free the slaves. Brown was heading to Bleeding Kansas to spill more blood on Kansas soil.

“I have only a short time to live, only one death to die, and I will die fighting for this cause. There will be no peace in this land until slavery is done for.“

… John Brown, Kansas Territory, 1856.

The Sack of Lawrence, Kansas – A Step Toward A Civil War

Lawrence, Kansas was a small anti-slavery town founded in the fall of 1854 near the Missouri border. The town grew and by spring of 1856 Lawrence could boast of 1,500 residents. On May 21, 1856, over 800 Missouri “Border Ruffians” and other newly arrived pro-slavery supporters surrounded Lawrence and plundered the town as citizens fled for safety. The Border Ruffians were flying various flags of pro-slavery sentiment, one such was a red flag with the words “Southern Rights.”

The pro-slavery men first tried to destroy the Free State Hotel in Lawrence with cannon fire from “Old Sacramento,” a cannon taken by pro-slavery forces from the Liberty Arsenal in 1855, but the cannon failed to achieve the desired result so they set the hotel on fire. The office of the Lawrence newspaper Herald of Freedom was destroyed by the pro-slavers, the newspaper printing press smashed, and the printing type thrown into a river. The pro-slavery invaders blocked and guarded the roads to Lawrence and then looted the town, helping themselves to the possessions of the citizens. Only one death occurred during the Sack of Lawrence. A pro-slavery man was killed when part of the Free State Hotel collapsed on him. Kansas would remain a hotbed of pro-slavery and anti-slavery violence and disorder right up until the start of the Civil War.

What Was John Brown’s Pottawatomie Creek Massacre?

John Brown’s Kansas settlement, home, and headquarters were located nearby to Lawrence at what was known as Brown’s Station. At Brown’s Station Captain John Brown (as he was now referred to, the rank not being an official military designation) had some of his sons, other men, and weapons, all ready to advance the cause of Kansas becoming a free state by using violence.

Captain John Brown was on his way to Lawrence to help defend it from the Border Ruffians when news of the town’s sacking reached him. When he learned the town was taken by the Border Ruffians without any resistance from its citizens, Brown angrily exclaimed, “Had no one put up a fight?” Later, as Brown’s band of men were camped, Brown was talking with others about pro-slavery settlers at nearby Dutch Henry’s Crossing. It was overheard as Brown spoke, “Now something must be done, something must be done now.”

John Brown would lead eight men armed with the rifles, revolvers, and ominous, medieval-looking short, heavy broadswords, that Brown had brought with him from Ohio. Before leaving for Dutch Henry’s Crossing they took time to sharpen the blades of the broadswords. Son Owen Brown (named for his Hudson, Ohio grandfather) was a member of the eight-man party heading for Dutch Henry’s Crossing. Young Owen later explained, “There was a signal understood, when my father was to raise a sword–then we were to begin.”

James P. Doyle, William Doyle, and Drury Doyle

The Doyles were in bed on the night of May 24, 1856. There was a sound from the yard and then a knock at their cabin door. The Doyles were poor and illiterate folks from Tennessee who lived on a tributary of Pottawatomie Creek named Mosquito Creek. They were pro-slavery, but owned no slaves. Father James went to the cabin’s door and a voice from outside asked him for directions to a neighbor’s home. James begins to open the door but men armed with pistols and swords barge in. The intruders announce they are taking James and three of his sons as prisoners.

Wife and mother Mahala begs the rough men with eastern and northern-like accents not to take her youngest son, sixteen-year-old John. The men allow John to stay with his mother. They ask where they could find Allen Wilkinson’s home, the Wilkinsons lived about a half mile away from the Doyles. Captain John Brown and his men take James and the two oldest sons outside. Soon there is a gun shot. Mahala would later say, “My husband and two boys, my sons, did not come back.”

At dawn the following morning Mahala and son John cautiously go outside their cabin. About two hundred yards away down the road John finds the bodies of his father and two brothers. All of the bodies have gruesome wounds. Twenty-two-year-old brother William lies dead with his head sliced open, his jaw and side slashed. John’s twenty-year-old brother Drury is found lying nearby. Drury’s body has fingers missing, his arms are sliced off, there is a hole in his chest, and his head is cut open. Father James has been shot in the head and stabbed in the chest. Anti-slavery and abolitionist John Brown and his men have spilled their blood and taken their lives.

James Hanway was an anti-slavery man who lived in Shermansville, a small place in Franklin County, Kansas. Hanway wrote an account what John Brown and his men did at Pottawatomie Creek, His account includes, “old man Doyal was shot through the head & stabed through the heart & his 2 boys where disherated cut about the hands – the younger boy’s hands were mangled as if he had held up his hands to defend himself from the blows of the saber.”

Allen Wilkinson

That night at Allen and Louisa Jane Wilkinson’s cabin she was ill with the measles. It was after midnight and their two children were in bed. Allen was a notable citizen of Pottawatomie Creek. Both Allen and his wife could read and write and he was a member of Kansas’ pro-slavery legislature. The Wilkinson cabin doubled as a post office. Like their neighbors the Doyles, the Wilkinsons were from Tennessee and did not own any slaves.

Louisa Jane heard their dog barking outside and woke her sleeping husband. Allen told her it was nothing to worry about. Soon the dog is barking again, but this time with greater anger and alarm. Now footsteps are heard coming from outside. A knock at the door and Allen inquires who is there. A man’s voice replies, “I want you to tell me the way to Dutch Henry’s.” From inside the cabin Allen begins to give directions, but the man outside interrupts him and demands, “Come and show us.” The unseen man asks Wilkinson if he is against Kansas becoming a free state and Allen says that he is. Now Allen is told by the man outside the cabin door, “You are our prisoner.”

The cabin door bursts open and four men rush in. Allen Wilkinson’s gun is taken and he is told to get dressed. An old man seems to be in charge of the intruders and Louisa Jane implores him to leave her husband, that she is sick and has two small children. The old man asks if she has neighbors and Louisa Jane says she does but is too sick to go for them. “It matters not,” is the old man’s reply and her husband Allen is taken away into the night.

The next day people come to the Wilkinson cabin looking for their mail. They find Louisa Jane cowering in fear and crying. She was too terrified to go outside and look for her husband. Allen’s body is located about a hundred and fifty yards from the Wilkinson cabin. His body is in brush near the creek, his throat is sliced open and there are gashes on his head and side.

James Hanway wrote of Allen Wilkinson’s death, “Wilkinson – the latter received 6 wounds each one would have proved fatal,” and “One was flung in the Creek down the bank. (Wilkinson) he was post master.” Captain John Brown and his men with broadswords have added Allen Wilkinson to their victims of slaughter list that night along Pottawatomie Creek. So far, with the Doyles and Wilkinson, the death total is four. One more would make it five.

And Old Brown

Old Osawatomie Brown,

May trouble you more than ever, when you’ve

nailed his coffin down!

…From the book “A Voice From Harpers Ferry” by Osborne Perry Anderson.

William Sherman

Henry and William Sherman were German immigrants, two pro-slavery brothers with a reputation for drunkenness and being menacing toward those who were anti-slavery. Henry had a store and tavern along a ford of Pottawatomie Creek and the area was known as Dutch Henry’s Crossing. Pro-slavery men liked to gather there. Captain John Brown and his men with broadswords came to visit at Dutch Henry’s Crossing that night of slaughter along Pottawatomie Creek. By chance, Henry Sherman was away that night trying to find cattle which had wandered off. Straying cattle were a stroke of luck that would save Henry’s life.

At Dutch Henry’s Crossing was a one-room cabin belonging to an employee of Henry Sherman’s named James Harris. In the cabin were Harris, his wife and child, and two men who were spending the night. These men had come hoping to buy a cow. Henry’s brother William was in the cabin too.

In the dark hours of early morning Captain John Brown and his broadsword men force their way into the Sherman cabin. They take James Harris and the two cow buyers outside for questioning. Having passed the questioning satisfactorily enough to spare their lives, the three are taken back inside the cabin. William Sherman is next to be taken outside. Some of Brown’s men are left to guard the cabin.

A short time passes and then a pistol shot comes from outside. The cabin guards leave, but first helping themselves to weapons, a horse and a saddle. Those remaining inside the Harris cabin spend the night in fear. When the sun comes up James Harris goes looking for William Sherman. He finds Sherman’s body lying in Pottawatomie Creek. Harris later testifies, “Sherman’s skull was split open in two places and some of his brains was washed out by the water,” and that, “A large hole was cut in his breast, and his left hand was cut off except a little piece on one side.”

Now there were five dead along Pottawatomie Creek in Kansas. All butchered by Captain John Brown and his men with broadswords. John Brown would not be brave enough to claim responsibility for the killings.

Brown’s son Jason had not been a member of his father’s Pottawatomie Creek broadsword gang. When Jason met up with his father he inquired:

“Did you have anything to do with the killing of those men on the Pottawatomie?”

“I did not do it, but I approved of it.”

“I think it was an uncalled for, wicked act.”

“God is my judge, we were justified under the circumstances.”

John Brown believed he was doing God’s work when five pro-slavery men along Pottawatomie Creek were hacked to death by broadswords. In the time that followed, John Brown would seldom speak of the Pottawatomie Massacre. He was reluctant to talk of what happened and of his part in the killings. If he did talk, then his explanation would be foggy and without clear admittance of his actions and guilt. He would say that he did not shed blood but was the leader. Does that wash him clean of guilt?

John Brown’s son Salmon was a member of the broadsword gang and he said, “Father never had anything to do with the killing but he run the whole business.” Salmon would also say, “The work was so hot, & so absorbing, that I did not at the time know where each actor was, exactly, or exactly what each man was doing.”

When Salmon Brown was an older man he told an interviewer and researcher that he had lied when he said his father had no active part in the killings of the Pottawatomie Massacre. He said his father had shot Allen Doyle in the head after he’d been killed by broadswords. In an odd explanation, Salmon said that the shot fired by John Brown into the dead Allen Doyle’s head was meant as a signal shot to the murdering party to gather and return to camp. Why would the signal shot be fired into a dead man’s head and not into the air or ground?

James Townsley drove a wagon for John Brown and his men the night of the Pottawatomie Massacre. Years later Townsley said John Brown killed Allen Doyle with a pistol shot. He claimed that Brown’s sons Frederick, Owen, Salmon, and Oliver killed William and Drury Doyle with broadswords. Another member of the Pottawatomie Massacre party was Thomas Weiner.

“Talk, is a national institution, but it does not help the slave.”

… John Brown.

And Old Brown

Old Osawatomie Brown,

May trouble you more than ever, when you’ve

nailed his coffin down!

…Anderson’s “A Voice From Harpers Ferry.” Earlier in his abolitionist career, John Brown was in Osawatomie, Kansas and there he murdered five pro-slavery men with help from four of his sons. This was Brown’s response to the pro-slave raid made on Lawrence, Kansas in 1856.

Did Kansas Become A Slave Or A Free State?

Bleeding Kansas was like a rehearsal for the Civil War. It was a place where anti-slavery and pro-slavery forces violently fought against each other civil war-like to decide whether or not a land would be free or slave. Kansas entered the Union as a free state on January 29, 1861.

Kansas In The Civil War

During the Civil War approximately 20,000 men from Kansas fought for the Union in nineteen infantry regiments and four artillery batteries. Union Kansas troops fought at Wilson’s Creek, Vicksburg, Chickamauga, Franklin, and Nashville. Approximately 1,000 Kansas men fought for the Confederacy and were known for guerrilla warfare, lawlessness, and bushwhacking. Famous Kansas bushwhackers include, William Clarke Quantrill, William T. “Bloody Bill” Anderson, and Jesse James. On the pro-Union guerrilla side, Kansas Red Legs and Jayhawkers made their raids on pro-slavery people, farms, and towns.

In August 1863 William Clarke Quantrill and approximately 400 pro-slavery men from Missouri staged a deadly and notorious guerrilla raid on Lawrence, Kansas. Quantrill and his raiders had a list of men to kill. When the Lawrence Massacre was over, 150-plus Kansas anti-slavery men or boys lay dead. The Civil War Battle of Mine Creek (or the Battle of the Osage) took place on October 25, 1864. It was a Union victory.

“The meteor of the war.”

…Author Herman Melville speaking of John Brown.

Related Posts:

Free And Slave States Map – State, Territory, And City Populations

Thirteenth Amendment Abolishes Slavery

John Brown Quotes

1850 Fugitive Slave Law

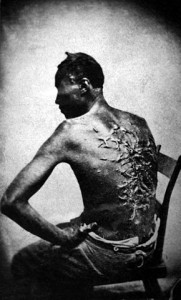

Slavery

Freedman Jourdon Anderson Writes A Letter To His Old Master

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!

My book 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes features quotes made before, during, and after the Civil War. Each quote has an informative note to explain the circumstances and background of the quote. Learn Civil War history from the spoken words and writings of the military commanders, political leaders, the Billy Yanks and Johnny Rebs who fought in the battles, the abolitionists who strove for the freedom of the slaves, the descriptions of battles, and the citizens who suffered at home. Their voices tell us the who, what, where, when, and why of the Civil War. Available as a Kindle device e-book or as a paperback. Get 501 Civil War Quotes and Notes now!