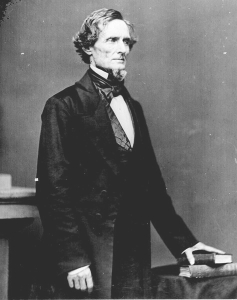

Various interesting notes about Jefferson Davis, and the Confederate States of America… with some Union history thrown in for good measure too:

- Jefferson Davis was born in Kentucky on June 3, 1808. A curious fact of the year 1808 (especially when you consider what Jefferson Davis’ life would mean to the Confederacy, slavery, and the history of the United States), is that in 1808 the importation of slaves was made illegal in the United States of America.

- Jefferson Davis was a graduate of the United States Military Academy (West Point). Davis ranked 23rd in his 33 member class of 1828. Also graduating in the 1828 West Point class was Robert E. Lee.

- After West Point, Davis was posted to the Pacific Northwest, serving there in the infantry. Davis transferred to the dragoons in 1833. After spending two years with the dragoons, Davis resigned as a first lieutenant.

- Jefferson Davis married Sarah, she was the daughter of Colonel Zachary Taylor, Davis’ commander. Colonel Taylor did not approve of his daughter marrying Jefferson Davis. Sadly, a short three months after they married, she died of malarial fever. Later, Davis would marry Varina Howell.

- Jefferson Davis took part as an officer in the Black Hawk War during the 1830s. Another officer in the Black Hawk War was Abraham Lincoln.

- Davis served from 1845 to 1847 in the House of Representatives as a Democrat.

- Davis fought in the Mexican War as a colonel of the 1st Mississippi Rifles. He was wounded at Buena Vista, and he declined a commission as a brigadier general. He then served in the United States Senate until 1853 when he became Secretary of War under Franklin Pierce. After Pierce’s presidency, Davis returned to the Senate.

- While he was Secretary of War, Davis imported camels and sent them to Texas. Davis thought the camels would do well in the arid environment of Texas and could be used as beasts of burden. The camels would be used to haul supplies and equipment for the United States Army troops in Texas. The Texas camels idea did not work out as Davis had hoped.

- Jefferson Davis and his wife, Varina Howell Davis, had four children. They lost their first child in infancy and then lost a son. Five-year-old Joe Davis fell from a balcony of the Confederate White House and died. Davis had the balcony torn down.

- After the Mexican War, Ulysses S. Grant was stationed in California. He was without his wife and children, and bored in California. Grant took to excessive drinking. Grant resigned his commission in 1854 and his resignation was accepted by the United States Secretary of War. The Secretary of War accepting Grant’s resignation from the United States Army was Jefferson Davis.

- Jefferson Davis was a strong supporter of states’ rights and supported his state of Mississippi’s secession from the Union.

- Mississippi seceded from the Union on January 9, 1861. On January 21, 1861 Davis was at the Capitol in Washington. History was about to happen. The Senate chamber was filled with curious on-lookers. On this morning, five senators from states that had seceded from the Union were to say their farewells. These senators were from the states of Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi. Jefferson Davis was among them. Davis rose and gave a stirring and emotional good-bye speech. He had been ill for a week and in bed. Davis had not slept the night before and was suffering from severe migraine head-aches.

- Montgomery, Alabama was the first capital of the Confederacy. On February 4, 1861 delegates from six of the states that seceded, met in Montgomery. Meeting at Montgomery, the Confederate States of America adopted a provisional constitution and also elected Jefferson Davis as provisional president. On May 20, 1861 the Confederate capital was moved to Richmond, Virginia. Montgomery only had two hotels, one of them was not up to desirable standards. The capital building in Montgomery was a bit small for the needs of the new Confederacy. Lack of adequate and decent hotel rooms and the need for a larger building in which to conduct the business of the Confederacy were some of the reasons for the move to Richmond.

- In February of 1861, at Montgomery, Alabama, Jefferson Davis was inaugurated as the provisional president of the Confederacy. On February 22, 1862 in Richmond, Virginia (where the Confederate capital now had been moved), Davis was inaugurated as the president of the Confederate States of America. The Confederate president was to serve a six-year term.

- Davis did not necessarily want to be president of the Confederacy. He would have preferred instead, to serve in the military and possibly command the Confederate army. As the events of the Civil War played out, Davis’ six-year term as the Confederacy’s president would be cut short.

- The White House of the Confederacy was the executive mansion for Confederate States of America President Jefferson Davis and his family. It is located in Richmond, Virginia. The Virginia State Capitol was the Capitol of the Confederacy.

- “Dixie” was the unofficial anthem of the Confederacy. When Confederate President Jefferson Davis and Vice President Alexander Stephens rode to their inaugural, a band played “Dixie.”

- Confederate postage stamps used only the portraits of President Jefferson Davis, General Thomas Jonathan “Stonewall” Jackson, or Senator John C. Calhoun.

- Jefferson Davis delivered his inaugural address from the Washington statue on the grounds of the Capitol of the Confederacy.

- St. Paul’s Church in Richmond, Virginia became known as the “Cathedral of the Confederacy” because both Confederate President Jefferson Davis and General Robert E. Lee attended church services there.

- Confederate President Jefferson Davis was attending church services at the “Cathedral of the Confederacy” in Richmond on Sunday April 2, 1865. During the church service Davis was given a note informing him that General Robert E. Lee’s lines had been broken at Petersburg. It was immediately time now, for the Confederate president to evacuate Richmond.

- Union troops occupied Richmond, Virginia on April 3, 1865. The Confederate capital of Richmond had fallen. President Abraham Lincoln went to Richmond the following day and visited the White House of the Confederacy. This visit to Richmond was a moment of glory for President Lincoln. The South was very near defeat, the Union was to be preserved, and slavery was to end. Lincoln saw Jefferson Davis’ office and took the opportunity to sit in Davis’ chair.

- Accompanying Lincoln in Richmond was his 12-year-old son, Tad. This was to be Lincoln’s first and last visit to Richmond. Lincoln died on April 15, 1865, the victim of an assassin’s bullet. Tad Lincoln would die of tuberculosis in 1871.

- After the South surrendered and the Civil War was lost for the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis was captured by Federal cavalry on May 10, 1865. He was accused of treason. On May 22, he was sent to prison at Fort Monroe, Virginia. Davis was kept there without benefit of a trial, for two years. Fort Monroe is the largest stone fort ever built in the United States. It is named for President James Monroe.

- Jefferson Davis died at New Orleans on December 5, 1889. Davis and his family, General J.E.B. Stuart, and General George Pickett are all buried at the Hollywood Cemetery in Richmond, Virginia. Over 18,000 Confederate soldiers rest in peace at Hollywood Cemetery. The cemetery is so named because of its many holly trees.