June 6, 1864

During May and June of 1864, Grant’s Army of the Potomac and Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia fought a series of battles in Virginia, which included The Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor. General Ulysses S. Grant was on the attack and his goal was to destroy the Army of Northern Virginia. Cold Harbor was fought on June 1-3, 1864.

Note: the term “cold harbor” meant a place to stay overnight, but where no cooked or hot meals are served. This is how the town of Cold Harbor got its name.

Overall, during this campaign of May and June in 1864, Grant’s Army of the Potomac was always moving to its left, hoping to flank the Army of Northern Virginia on its right. In early June, with the give and take of battle, the two armies were in a race to see which one would get to the crossroads town of Cold Harbor first. Lee won the race to Cold Harbor, but Grant was right behind.

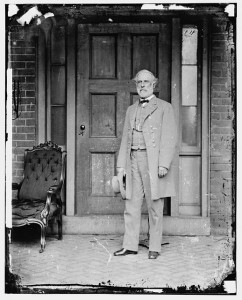

General Robert E. Lee was (as usual) outnumbered. At Cold Harbor Lee had 59,000 troops facing 109,000 Yankees. The previous four weeks of fighting had taken a considerable toll on both armies. The Union suffered casualties of 44,000, while the Confederates had casualties of 25,000. General Grant’s idea was to wear Lee’s army down by constant fighting, and cause Lee to lose by attrition. Grant knew by steadily forcing Lee to fight, and to continue to fight, eventually the superior numbers of men and firepower of the North would win the war against the Confederacy. If the Army of Northern Virginia could be ground down to a nub, the Confederacy would be defeated. Grant’s plan was working.

On June 3, at Cold Harbor, the Army of the Potomac faced a well-entrenched Army of Northern Virginia that held a good, strong, and defensive position. A newspaper reporter described the Confederate trenches as “intricate, zig-zagged lines within lines, lines protecting flanks of lines, lines built to enfilade opposing lines…works within works and works without works.” Their ranks contained seasoned soldiers who knew how to fight. Though outnumbered, the trenches gave the Confederates the advantage. At dawn, General Grant sent three Federal corps in a straight-on charge against the defensively entrenched Confederates.

This charge resulted in one of the bloodiest slaughters of the Civil War. Within only seven to eight minutes, seven thousand Union men fell at Cold Harbor. The dead and wounded covered a battlefield of five acres. A Confederate general commented; “I had seen the dreadful carnage in front of Marye’s Hill at Fredericksburg, but I had seen nothing to exceed this. It was not war; it was murder.” The amount of fire the Confederates poured into the Union soldiers was enormous. An Alabama colonel who witnessed the slaughter described a common end to the lives of many Union soldiers in this way; “dust fog out of a man’s clothing in two or three places at once where as many balls would strike him at the same moment.” A few men from a Zouave unit managed to come close to the Confederate lines, but soon shot down. A Zouave regiment colonel was struck by so many bullets that afterwards his remains could only be identified by brass buttons, which remained on what little was left of his officer’s uniform.

Grant knew by the afternoon he had lost, and no further attacks occurred. Cold Harbor was a Confederate victory. On the evening of June 3, Grant said; “I regret this assault more than any one I have ever ordered.” Grant knew his decision of a frontal charge at Cold Harbor was a mistake.

Petersburg was next for the two opposing armies.