They Called It “Hellmira”

It was called Hellmira by its inhabitants for a good reason. Of the 12,123 Confederate soldiers who were prisoners of war at Elmira Prison in Elmira, New York from July 6, 1864, to July 11, 1865, 2,963 of them died. That’s nearly a 25% death rate, one in four prisoners at Elmira Prison died. That is more than twice the average death rate of the other Northern prisoner of war camps, and in comparison, Andersonville, the brutal Southern prisoner of war camp had a death rate of 27%. Elmira Prison’s death rate was only 2% lower than Andersonville’s. Terrible living conditions, disease, and starvation caused Elmira Prison’s high death rate.

Elmira Prison was a hell.

The Creation Of The Elmira Prison Of War Camp

Early in the Civil War prisoner exchanges were common, but in 1863 a problem arose when the South said that captured black Yankee soldiers would not be treated and exchanged the same as white prisoners because they were probably ex-slaves who belonged to their masters, not the Union Army. The Confederacy needed prisoner exchanges much more than the Union did because it simply did not have as many men to lose as the Union. General Ulysses S. Grant realized that the Union prisoner of war camps held more prisoners than the Confederate prisoner of war camps, he thought this “prisoner gap” was an advantage for the Union. Grant ended prisoner exchanges until the end of the war was in sight. Since Confederate prisoners of war were no longer exchanged, the North needed more prisoner of war camps in order to hold the rebel prisoners.

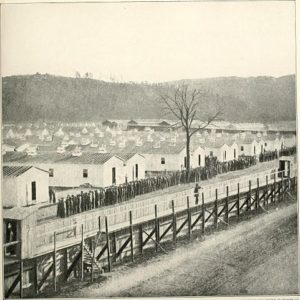

In 1864 Elmira Prison was made out of part of unused Camp Rathbun, which was a 30 acre Union army training camp located between the Chemung River and Water Street in Elmira, New York. Elmira was chosen for the army training camp because the nearby Erie Railway and Northern Central Railway lines made it easy to transport new army recruits to the training camp. By July 1864, Camp Rathbun was no longer used. Lieutenant Colonel Seth Eastman was in command of Camp Rathbun, he received word from United States Commissary-General of Prisoners Colonel William Hoffman to “set apart the barracks on the Chemung River at Elmira as a depot for prisoners of war.” The nearby railroad lines also made it easy for prisoners of war to be transported to Elmira Prison.

Elmira Prison Management

Elmira Prison camp was inspected by Surgeon Charles T. Alexander five days after it opened. Alexander reported two major problems:

- The camp’s sanitary conditions were unsatisfactory. Hoffman Pond within the camp and “sinks” near the pond were used to bathe, for drinking water, and as a toilet. The sinks were full of stagnant water and Alexander believed that they could; “become offensive and a source of disease.” He wanted new sinks to be made. But, United States Commissary-General of Prisoners Colonel William Hoffman didn’t listen to Alexander’s recommendation. No new sinks were constructed.

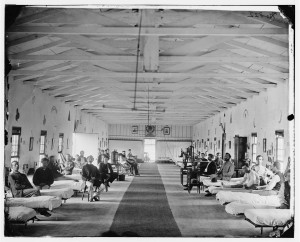

- Alexander did not like that the Elmira Prison hospital was merely a tent. He recommended a permanent structure be made for the use of the hospital. Three pavilion hospital wards were approved by William Hoffman with Alexander being responsible for their planning. Alexander also did not like that the prison camp did not have a surgeon assigned to it. Instead, Elmira Prison used the services of William C. Wey, who was a local Elmira citizen.

Elmira Prison Life And Death

Elmira Prison was surrounded by a stockade, inside there were 35 barracks which were only meant to house 5,000 prisoners. Elmira Prison’s kitchens could feed 5,000 a day and the mess room could seat 1500 at a time. Elmira Prison was overcrowded right from the start. On July 6, 1864, the first 400 prisoners arrived and by the end of the month, there were over 4,400 prisoners, with more of them soon on the way. By the end of August 1864 Elmira Prison had nearly 10,000 prisoners, double the number of prisoners it was meant to hold. The facilities were inadequate and the overflow of prisoners meant that many ended up sleeping in torn, tattered, and worn clothing on the open ground without blankets. The prisoners of war at Elmira Prison would suffer from the heat of summer and the cold of winter.

Day to day life for the Elmira prisoners was dull, some found ways to occupy their time by making trinkets out of bone or animal hair which the camp guards would sell in town. Boredom would be a minor problem for the prisoners, survival would be their greatest concern.

The death number in July, 1864 at Elmira Prison was 11, but by the end of August the number of deaths had grown to 121. Poor sanitary conditions in the camp led to disease. Foster’s Pond was within the camp and nearby it there were “sinks” used by the prisoners. Sinks were latrines contaminated by human waste. The unclean and stagnant water of the sinks and Foster’s Pond made the prisoners sick. Diarrhea, pneumonia, smallpox, and common maladies such as colds or simple cuts that became infected, all killed the Elmira prisoners. There was not enough meat and vegetables to feed the overpopulated prison. The food was in short supply and prisoners became malnourished, which only weakened prisoners more and made them susceptible to disease. In September 1864 there were 1,870 cases of scurvy. Following scurvy, there were epidemics of diarrhea, then pneumonia, and then smallpox. At the end of 1864, 1,264 prisoners of war had died at Elmira Prison. The prison was a death camp and the surviving prisoners began calling it “Hellmira.”“The drainage of the camp is into this pond or pool of standing water, and one large sink used by the prisoners stands directly over the pond which receives its fecal matter hourly… Seven thousand men will pass 2,600 gallons of urine daily, which is highly loaded with nitrogenous material. A portion is absorbed by the earth, still, a large amount decomposes on the top of the earth or runs into the pond to purify.”

… Surgeon Eugene F. Sanger referring to Foster’s Pond after a camp inspection.

The 1864-1865 winter of Elmira, New York was a particularly cold and bitter one. The temperature twice fell to -18 degrees Fahrenheit and a storm in February brought over two feet of snow. This winter weather was tough enough on Northerners, but the captive Southern men without adequate winter clothing or shelter at Elmira Prison had never experienced such cruel cold before, it was a harsh shock to their constitutions and health. United States Commissary-General of Prisoners Colonel William Hoffman would not allow clothing sent from the South to be given to the prisoners unless it was gray in color. Other colored clothing sent from the South was burned while the prisoners it was meant for literally froze to death.

Elmira Prison Facts

- Major Henry V. Colt was Elmira Prison’s first commander. Colt happened to be the brother of Samuel Colt, who is famous for the Colt pistol.

- Seventeen men escaped from Elmira Prison, once ten escaped at the same time. Tunnels were the method of escape and some were dug under the camp hospital.

- Barry Benson is one of the men who escaped from Elmira. Benson is noteworthy because after the Civil War he wrote the bookConfederate Scout and Sniper which told of his experiences in the Civil War.

- An observation tower was built outside of the Elmira Prison boundary by an entrepreneur who placed advertisements in the newspaper. For ten cents a customer could climb the observation tower to peer down into the prison camp to see its suffering and horror. Other opportunists set up wooden booths to sell concessions of lemon pop, ginger cakes, beer, and liquor. Eventually, a second observation was built at the end of the wooden concession booths, but then that tower and the booths were ordered torn down by the camp’s commander. The first observation tower remained.

- The only surviving material of Elmira Prison is its flag pole. The flag pole was sixty feet tall during prison days, but in recent times a local homeowner used it to mount a TV antenna that was then struck by lightening. This trimmed the Elmira Prison flag pole to thirty feet, half its original height. The flag pole today is still there at the Elmira Prison, but it is not at its original center of the prison location.

- A smallpox epidemic hit the prison during the terribly cold winter of 1864-1865. Smallpox had no cure in Civil War times. Smallpox Island and Hospital was made on land forming an island across on the Chemung River. Elmira Prison smallpox victims were taken there to isolate them at a place where they could wait to die. In the first week of the smallpox epidemic 140 men died, or 20 a day. Smallpox continued to kill prisoners at Elmira Prison until the prison closed in July, 1865.

- United States Commissary-General of Prisoners Colonel William Hoffman ordered that rations for Elmira’s prisoners be cut to only bread and water. Hoffman was also known for being tight and stingy with money spent on Elmira Prison.

- There was room in the barracks for about 6,000 prisoners, most other prisoners were living in tents. By late November and early December 1864, over 2,000 prisoners were sleeping in tents during cold weather. On Christmas day an inspection revealed that 900 prisoners had no proper housing/shelter.

- The barracks at Elmira Prison fell into disrepair. By November 1864, their roofs were leaking and even falling, the prison barracks were unable to protect the prisoners from the winter cold, snow, and wet. There was a lack of lumber for barracks repairs or new construction.

- The original army training camp, Camp Rathbun, was also called Camp Chemung for the nearby river.

- Rats were valuable to the prisoners for purposes of trading. For example, a rat could be bartered for five chaws of tobacco or one haircut.

At the end of the Civil War, 2,963 Elmira prisoners had died due to disease, malnutrition, exposure, or other reasons directly related to prison conditions. Many of these deaths could have been avoided. The North was rich in food and supplies, not only for its armies and people but for the prisoners of war it held.

Runaway Slave John W. Jones Buried The Confederate Dead Of Elmira Prison

Jones Buried 2,973 Confederate Dead At Woodlawn Cemetery

John W. Jones was twenty-seven-years-old when he and four other slaves ran away from their master’s plantation in Leesburg, Virginia, fleeing 300 miles to Elmira, New York. In freedom, Jones made Elmira his home, he learned how to read and write, and became an active agent on the Underground Railroad. Jones helped over 800 runaways escape to freedom in Canada. He was contracted in 1864 to be the caretaker of Woodlawn Cemetery located one and a half miles north of Elmira Prison. John W. Jones was responsible for the work of burying the Confederate dead from Elmira Prison. He was good at his work.

Jones’ burial record-keeping was precise. Of the 2,973 Confederates he buried in Woodlawn Cemetery, only 7 of them were listed as unknown. Each wooden grave marker (The original grave markers were replaced with granite headstones in 1907.) included the dead’s name, his regiment, his company, and a unique grave number. This attention to detail makes it easy for family and researchers to locate graves at Woodlawn Cemetery. Jones buried the Elmira Prison dead respectfully and in a reverent way, but the work kept him occupied. One busy day, Jones buried 48 Elmira Prison dead. The number of burials made John W. Jones a prosperous man, he was paid $2.50 for each burial which was a notable amount during Civil War times. Jones became one of the most wealthy African-Americans in western New York.

John W. Jones is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery near the graves of prominent abolitionists.

Note: Woodlawn Cemetery contains the Woodlawn National Cemetery. Woodlawn National Cemetery is the section where the Elmira Prison Confederate dead are buried. The United States Veterans Administration is in charge of it.

Woodlawn National Cemetery

National Cemetery Elmira, NY-3,000 Confederate POWs Died

Note: The prison camp in Columbus, Ohio the video narrator refers to is Camp Chase.

Woodlawn Cemetery Confederate Monument

The United Daughters of the Confederacy erected a monument in the section of the Woodlawn Cemetery where the Elmira Prison Confederate dead are buried. An image on the monument shows a Confederate soldier gazing over the graves. The monument is inscribed:

IN MEMORY OF

THE CONFEDERATE SOLDIERS

IN THE WAR BETWEEN THE

STATES WHO DIED IN ELMIRA PRISON

AND LIE BURIED HERE.

ERECTED BY THE

UNITED DAUGHTERS OF THE CONDERACY

NOVEMBER 6, 1937

The End Of Elmira Prison

Robert E. Lee surrendered to Ulysses S. Grant at Appomattox on April 9, 1865. The last day of the prison camp was July 5, 1865, and the last Elmira prisoner departed the camp on September 27, 1865. Before their release, the prisoners had to take a loyalty oath and then they were given a train ticket to go back home. Elmira Prison was closed and demolished, it became farmland.

The place of Elmira Prison is now a residential neighborhood. There are plans in work to reconstruct the camp and to build a museum.

Elmira Prison Camp Building Reconstructed

A news report from August 4, 2015: